Reutter 2 Concertos in C major and D major

Instrumentation: Trumpet, Strings, B. c.Difficulty (I-VI): VI

Parts: Trumpet in C/D and high Bb/A, Strings 4324, B. c., Score

Series: Edward Tarr Brass

Editor: Edward H. Tarr

The Viennese court trumpeters played an important part in imperial displays of splendor. From 1623 onwards they had their own guild, with a Privilege signed by Emperor Ferdinand II himself and confirmed by all his successors up until Joseph II in 1767. The Privilege regulated instruction and ensured that trumpeters and timpanists "perform solely for the Emperor, Kings, Electoral and Imperial Princes, Counts and Lords of knightly rank, and similar persons of quality, and therefore do not belong in common to everybody“. The imperial court of Vienna was thus unreservedly the most important center of the Baroque trumpeters‘ art. (The second center was Dresden, where the Elector of Saxony was responsible for resolving any disputes arising in connection with the Imperial Privilege.) During the reign of Karl VI, the number of „Musical Trumpeters and Military Kettle- drummers“, who formed a part of the „Imperial Court and Chamber Musici“ and answered to the court musical director, grew from 14 to 18. A second group, known as the „Court and Field Trumpeters and Military Kettledrummers“ and responsible to the „Chief Quartermaster‘s Staff and Court Mess Office“, consisted of 17 to 26 members. It was possible for a trumpeter to belong to both groups. Additionally, there were further trumpeters in the Emperor‘s and Empress‘s Lifeguards. The court protocol („Rubriche Generali“) made it clear that on the most solemn feast days, „Gala Grande“ was called for, with two or four trumpeters and a timpanist joining the otherwise trumpetless orchestral forces. It was also the custom to perform great operas in this way on the Emperor‘s name-day and the Empress‘s birthday.

In the operas and church music of that time, obligato instruments, singly or in pairs, often joined forces with the solo singers in particularly brilliant arias; the trumpet was one of the most frequently employed solo instruments. In addition, the trumpet was often used solo in those instrumental compositions — concertos, sonatas, and ballets — written for religious or worldly events. Today these pieces, which hardly exist in modem editions and thus are still practically unknown, are a gold mine of passagework of the utmost virtuosity, in this respect even outshining the works of J. S. Bach. Both of Reutter‘s trumpet concertos, published here for the first time, represent the tip of this proverbial iceberg.

Johann Heinisch - Greatest Baroque Trumpeter? The names of several court trumpeters are recorded who produced such amazing feats, bringing the art of clarino playing to its fullest flower during the course of the 18th century. Franz Küffel was „Chief Trumpeter“ from 1711 to 1754. According to a testimonial of 1718 by court composer J. J. Fux, Franz Joseph Holland(t) is said to have „particularly distinguished himself on his instrument“; he was active at the Viennese court from 1711 until his death in 1747.

The greatest Viennese player of the natural trumpet of that day, and probably one of the greatest players of all times, was Johann Heinisch (Hanisch). The year of his birth is unknown, but he was probably a generation younger than his colleague, the Leipzig town musician Gottfried Reiche (1667-1734), who gave the premiere performances of most of J. S. Bach‘s trumpet parts. Heinisch appears in the archival records for the first time in 1726-27 as a „scholar“. He was hired provisionally to replace a deceased colleague in 1727, and permanently in 1730, although it is interesting to note that he was not listed at the outset as a „Musical Trumpeter“, since such a position was not vacant at the time. He died in 1750.

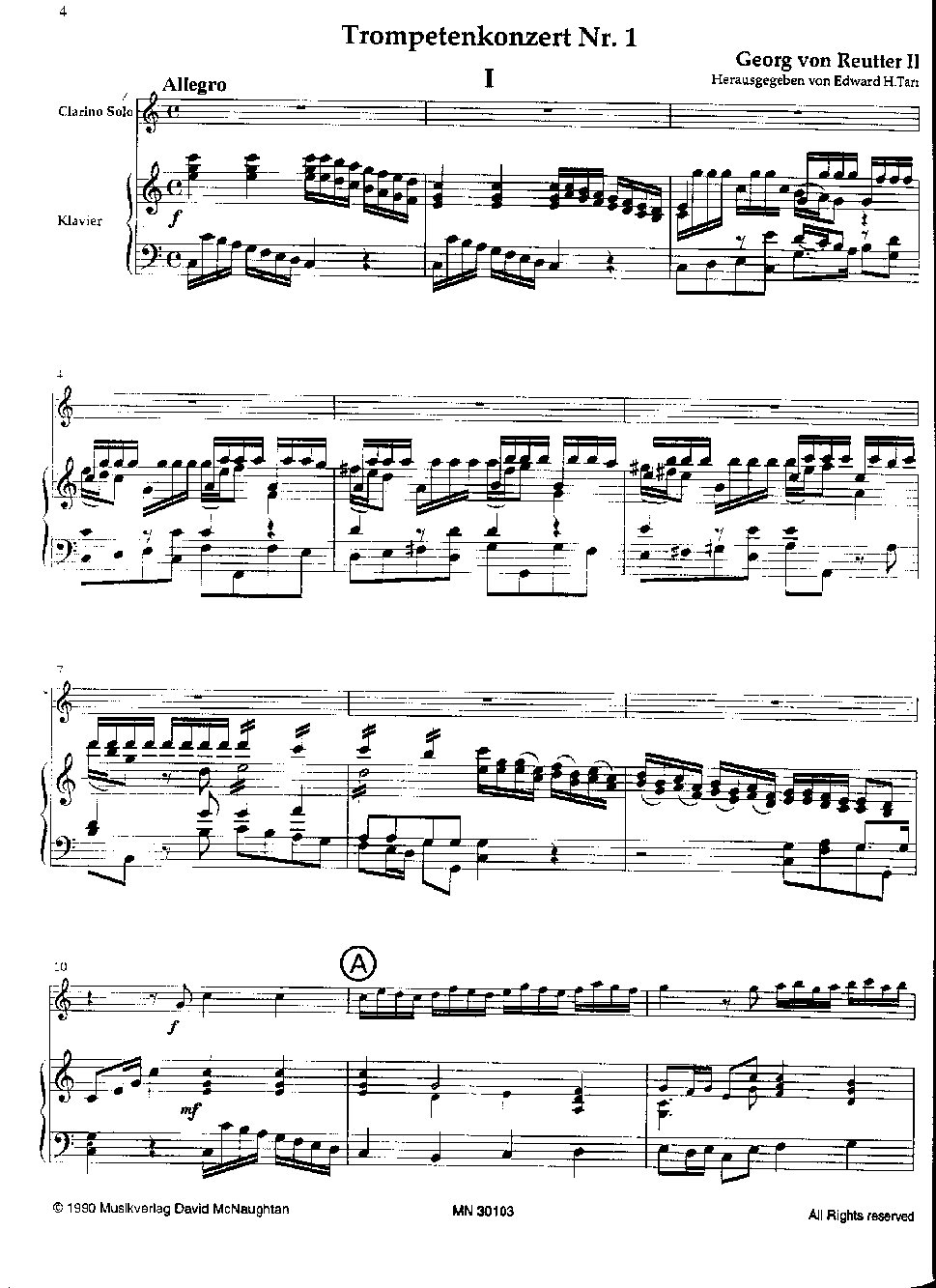

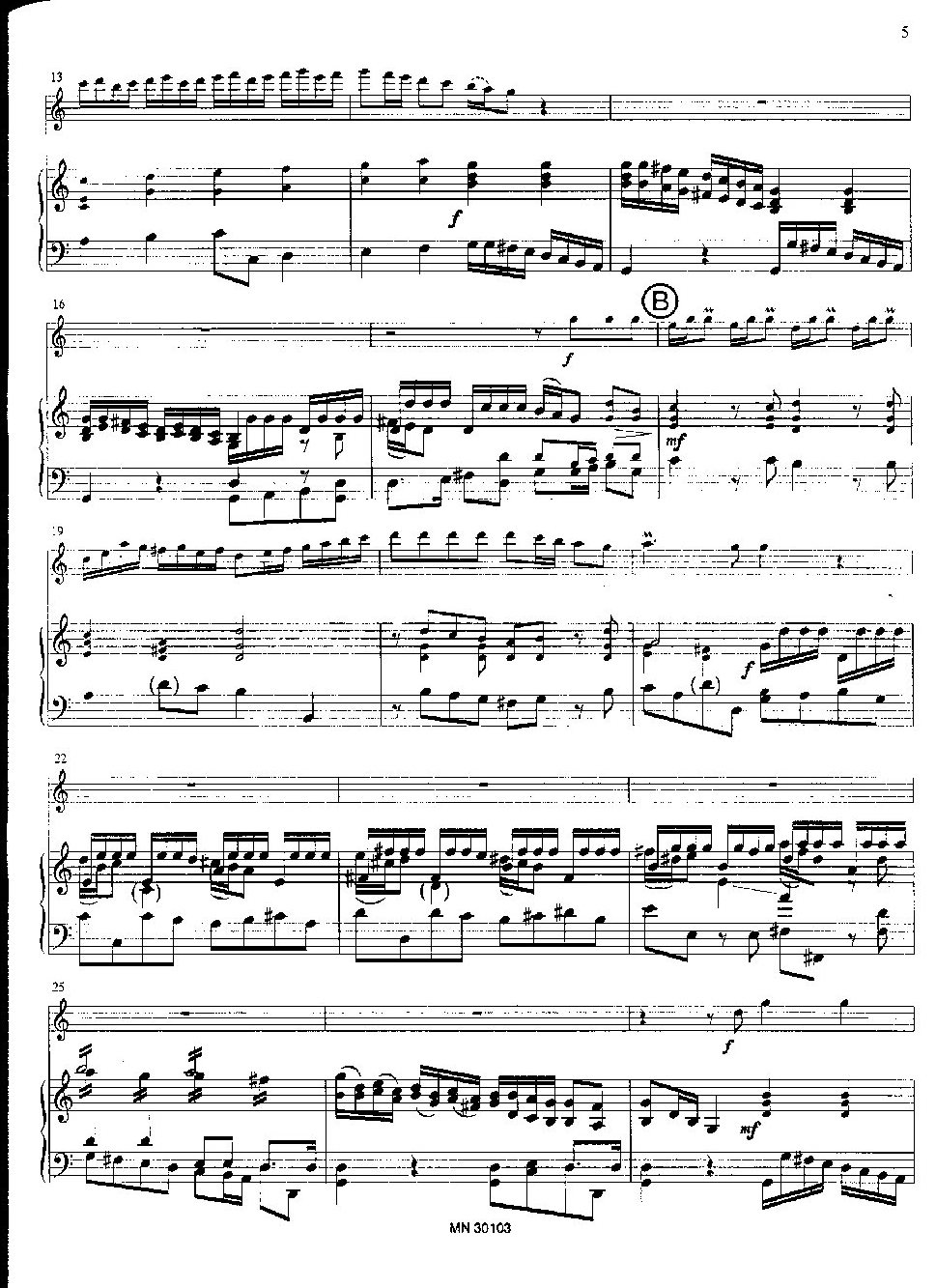

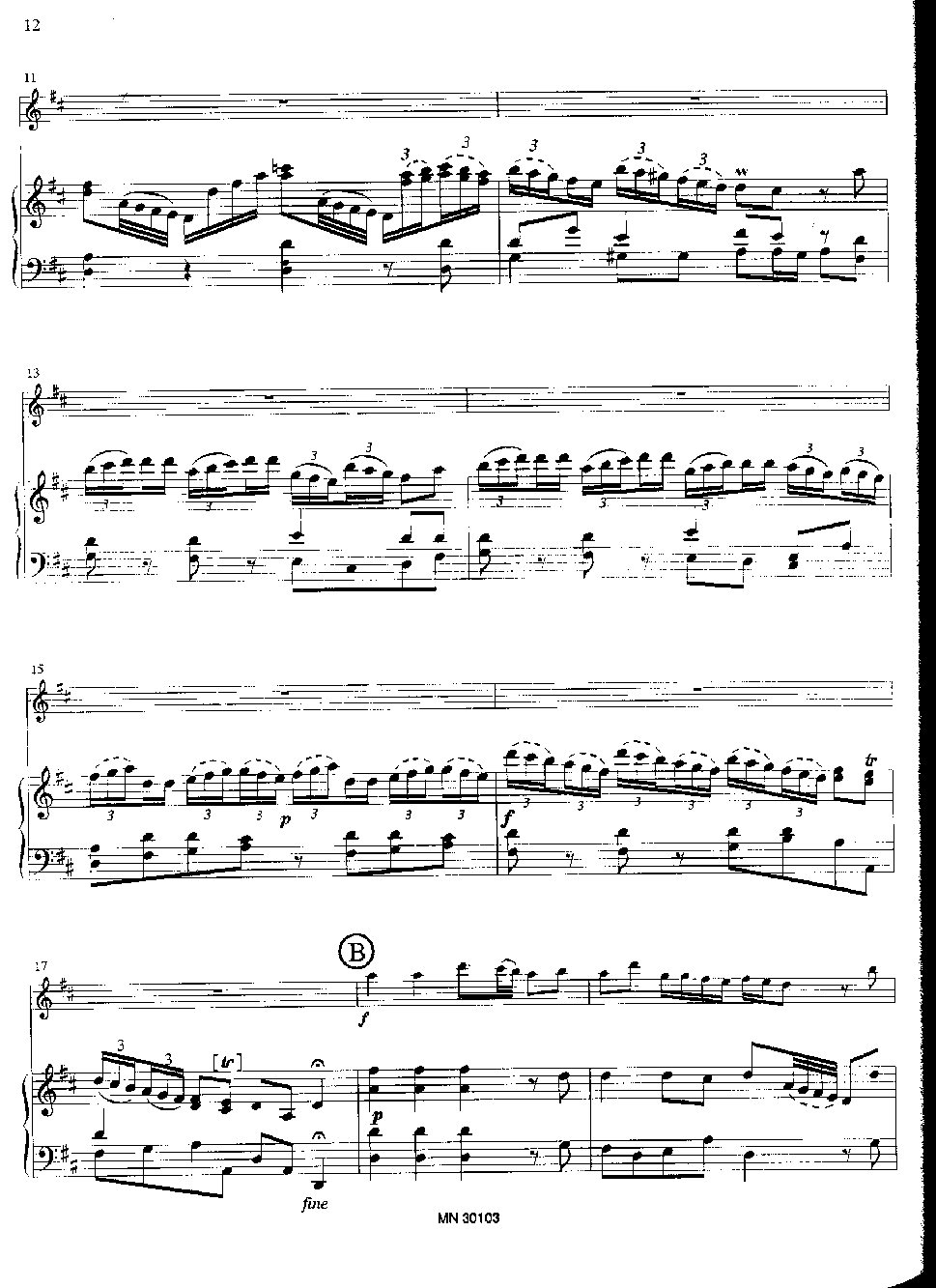

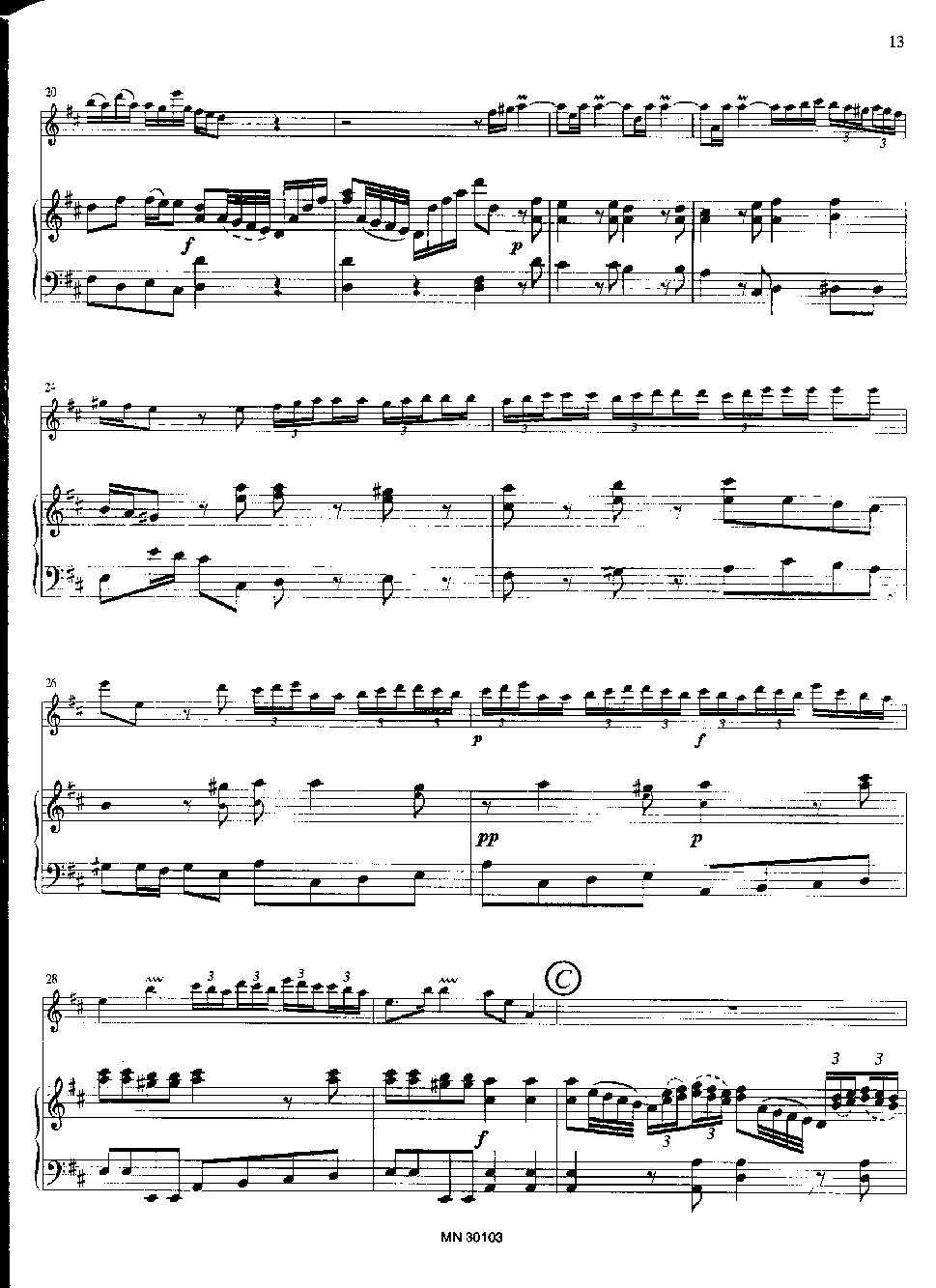

These concertos are unthinkable without the soloist Heinisch, although they differ stylistically from one another. Trumpet Concerto No. 1 in C was probably written in the 1730s and requires the soloist to ascend several times to the 24th note of the harmonic series, g“\ a height which is not reached merely once and slurred into from below, as it happens in the well-known D major concerto by Michael Haydn which until now was considered to be the „world record“ piece, but rather via leaps, and articulated several times in succession — pure wizardry. This unique height is reached twice in the first movement. Already in the first solo entry, Reutter‘s facile use of sequence can be observed: J. J. Quantz was of the opinion in 1752 — to be sure, he was writing about solo cadenzas — that sequence should be maximally used three

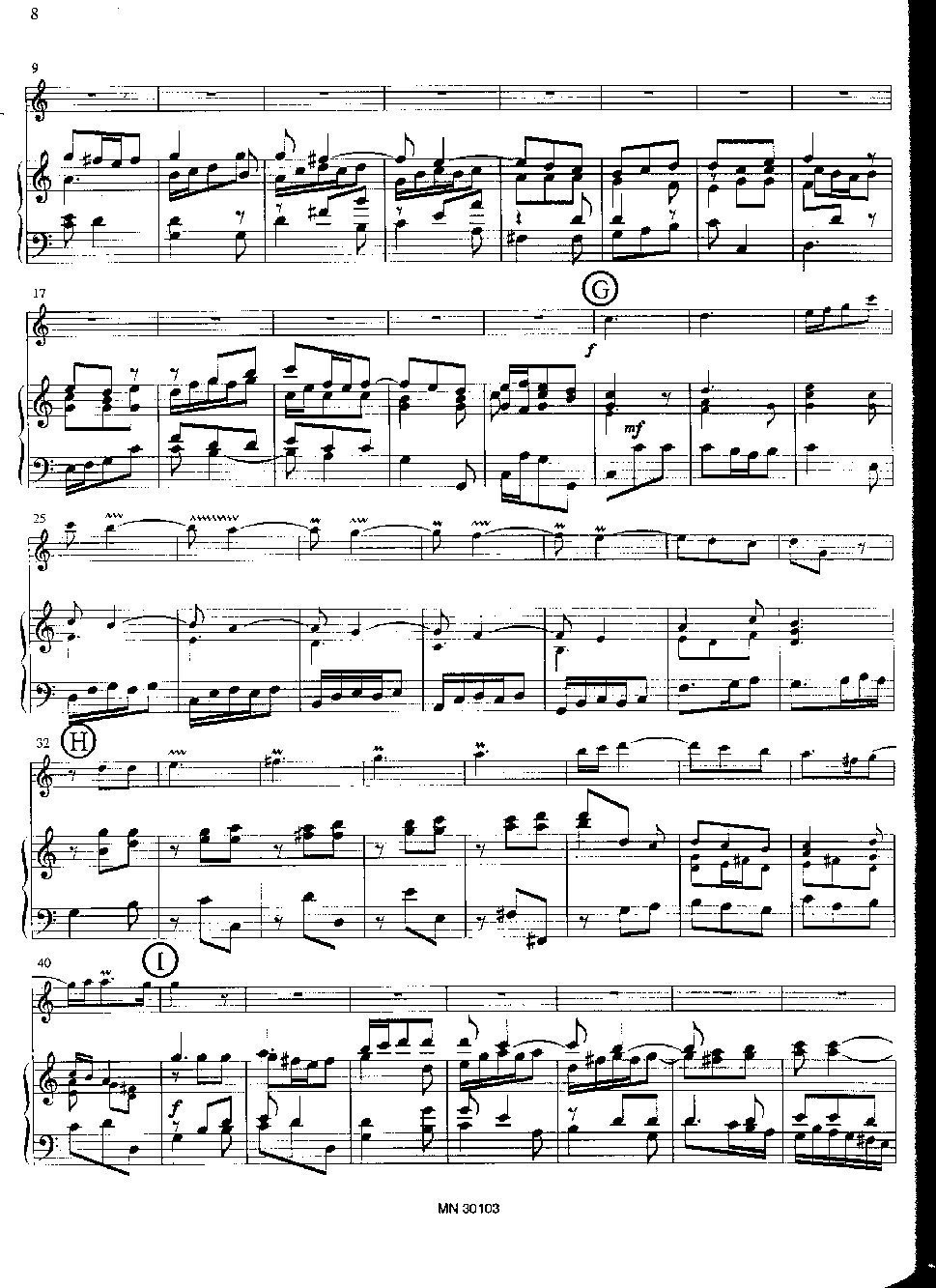

times, but already in the second bar, Reutter writes three sequences for the trumpet, with five in the next two bars. He takes the group of eight semiquavers at the end of bar 29 six times in sequence to the end! In the second movement of both this and the 2nd concerto, the trumpet is silent while the strings evoke Italianate melancholy. The third movement comports itself in the old fugal style, thus betraying the work‘s probable origin in a church celebration. Here the solo part „only“ goes up to e‘“, not to mention the concluding fermata-cadenza, which is to be improvised by the soloist and in which he is certainly free to go up still higher, if his lips will allow it...

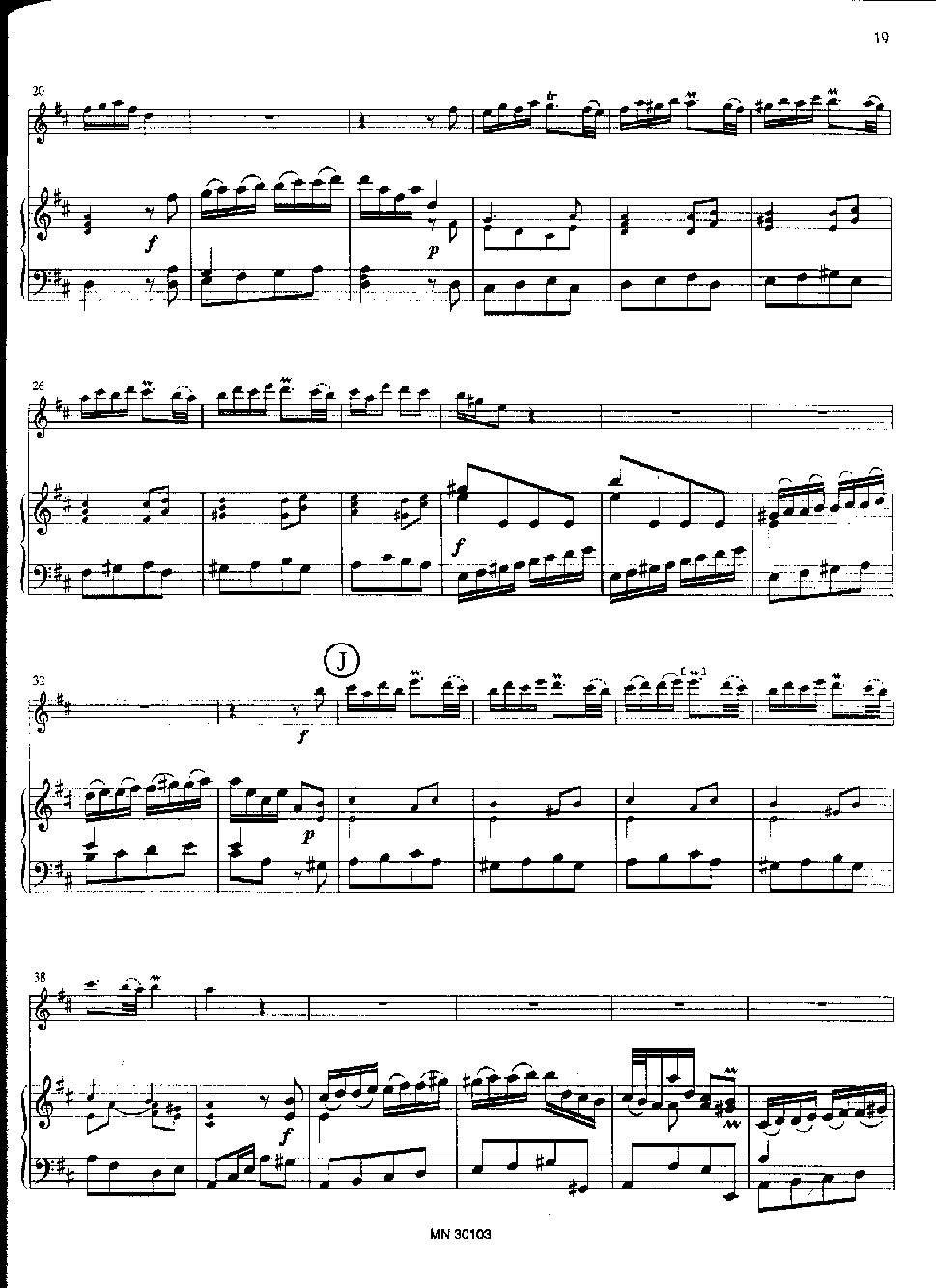

Trumpet Concerto No. 2 in D is in the more modern concerto style and was probably written in the 1740‘s. The violins bustle, and the solo part is technically still more demanding than in the 1st concerto, although it does not ascend as high here as there. (The range of this work goes up to the 18th partial, which of course sounds a tone higher, e‘“, than in the other work.) The phrases are longer and thus more strenuous, nearly every longish note is fitted out with a trill, through which performance difficulty is increased, and there are more arpeggios and other leaps, technical features which are particularly difficult on the natural trumpet of that day. The themes, particularly that of the third movement, would well befit a flute concerto, and we are reminded of the contemporary report on Heinisch, whose „trumpet behaved like a little flute“. I wish my trumpet-playing colleagues the world over lots of fun in the preparation of these not-so-easy pieces!